History proves that weeds continue to find ways to gain acres and evade control in new territories.

History proves that weeds continue to find ways to gain acres and evade control in new territories.

Most weed shifts today are likely due to extended use of the same herbicide(s) or tillage practice changes. Nevertheless, you need to keep a watchful eye for new weeds that invade from outside the Midwest and change your weed spectrum.

One notable shift was the rise of woolly cupgrass in the 1980s, which came from China and was first reported in Iowa in the 1950s, says Bob Hartzler, Iowa State University weed scientist. “It spread rapidly across the region since its large seed size was more tolerant of preemergence herbicides (like commonly used Dual and Lasso) than foxtails. Farmers even adopted continuous soybeans for two to three years to get woolly cupgrass under control with trifluralin/pendimethalin. When Accent and Balance were introduced, they provided better control in corn,” he says.

A current weed spectrum shift culprit is Palmer amaranth, a dioecious summer annual broadleaf pigweed from the desert Southwest. Before invading the Corn Belt, it caused significant economic crop losses in cotton and soybeans across the South and Southeast, while gaining resistance to glyphosate and ALS herbicides.

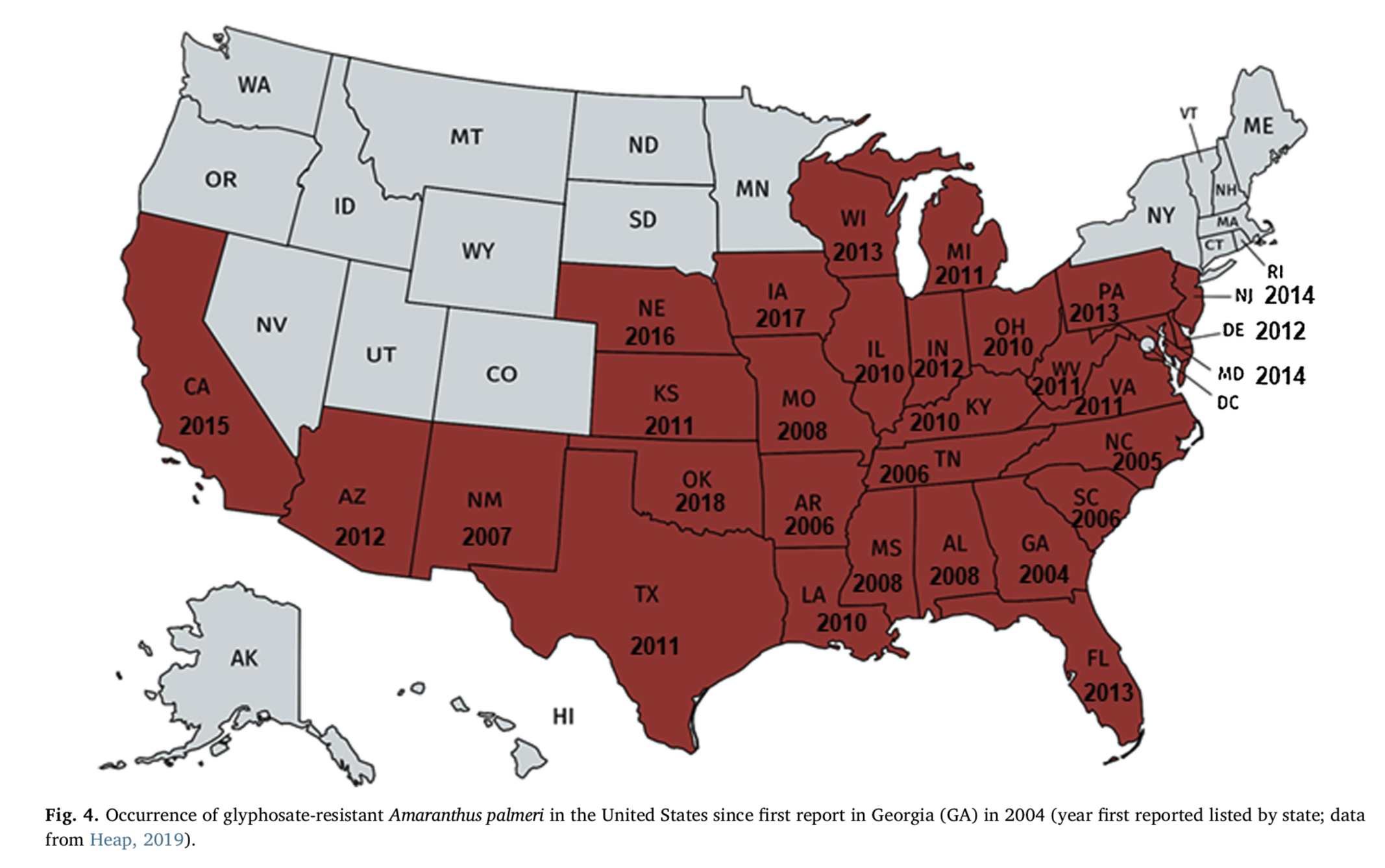

Palmer pigweed’s herbicide-resistant seeds have hitched a ride into the Midwest since 2008 (see map). These tiny seeds arrived in livestock feed ingredients (spread in manure), in native seed mixes for conservation and pollinator seedings, in used equipment and by custom combine cutters, and even spread by birds, mammals and ditch mowing.

Wind helps spread ample amounts of Palmer pollen from male plants to female plants that produce seed heads containing 200,000 to 1 million seeds per plant. Its rapid growth rate (up to 1 to 2 inches per day) and season-long germination challenge herbicide application timing.

Climate Change Expands Palmer Problem

As climate change influences temperature and rainfall patterns, both long-term signals (overall warming, more intense precipitation events) and short-term patterns are repeating themselves, says Adam Davis, head of the Department of Crop Science at the University of Illinois.

“Due to increasing weather volatility, colder wetter springs in the upper Midwest, followed by hotter, drier summers, we’re seeing southern weed species such as Palmer amaranth become increasingly common in the upper Midwest Corn Belt.”

Davis says these weedy amaranths (Palmer and waterhemp) have a lot of genetic diversity and a particular knack for evolving metabolic resistance to herbicides. That's resulted in multiple herbicide resistance in the region. “The success of this weed complex has meant the decline of other, less adaptable weed species such as velvetleaf, giant foxtail and giant ragweed, which used to dominate the weed communities of the northern Corn Belt," Davis points out.

Adopt New Weed Control Mindset

Palmer amaranth, like its cousin waterhemp, is now resistant to up to seven different herbicide sites of action (up to five-way multiple resistances in one population). Adopting a proactive management plan can help prevent future problems, says Karla Gage, weed scientist and plant biologist, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

“We have to shift our mindset to manage the seedbank, which begins with a solid and overlapping soil residual herbicide program,” Gage says. “A start clean, stay clean plan to prevent weeds from emerging is the best way to slow change in the weed seedbank community.”

While Gage says Palmer has been invading the Midwest, any grower doing a good job controlling waterhemp will likely succeed with Palmer. Similar tactics should work for both weeds, depending on herbicide resistance levels in both.

For more information, check out Corteva recommendations in “Palmer Amaranth in the North-Central U.S.”

Content provided by DTN/Progressive Farmer

The More You Grow

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.