Evolving Climate and Weeds Increase Corn Yield Risk

The goal is to stop weeds to preserve your corn crop’s yield potential. However, the process is often full of pitfalls as climate and weed species evolve each growing season.

Nature and farmer weed/crop management choices have increased resistance mechanisms in weeds to reduce herbicide effectiveness. Overuse of the same herbicide and/or mode of action, rate cutting, reduced crop rotation diversity, and reduced tillage have all contributed to selecting weeds that survive herbicide chemistries.

Critical driver weeds that emerge beyond the early season—like giant ragweed, waterhemp and Palmer amaranth—add seeds by the hundreds of thousands to the soil, often increasing input costs for up to seven years to get weeds under control.

Reliance on herbicide silver bullets is a thing of the past. As a result, researchers are applying machine learning techniques to decades of weed control efficacy data in the hope to model improved weed control practices.

USDA-ARS ecologist Marty Williams and University of Illinois weed scientist Aaron Hager began such a journey four years ago. “Since we’re office neighbors in Turner Hall, one day Marty stopped by to discuss a large data set he received,” Hager says. “With his expertise as a statistician, we kicked around many ideas and landed on combining it with our 27 years of university Herbicide Evaluation Program (HEP) data.”

To determine the most critical factors that can affect corn yield loss due to weeds, Williams enlisted crop scientist Christopher Landau (then a postdoc student) to analyze 3,000 individual small-plot HEP trials in 205 unique weather environments in Illinois (1992-2019).

Results from analysis of planting dates and population, hybrids, weed control by species, weather data by growth stage and yield have validated long-held weed scientist recommendations.

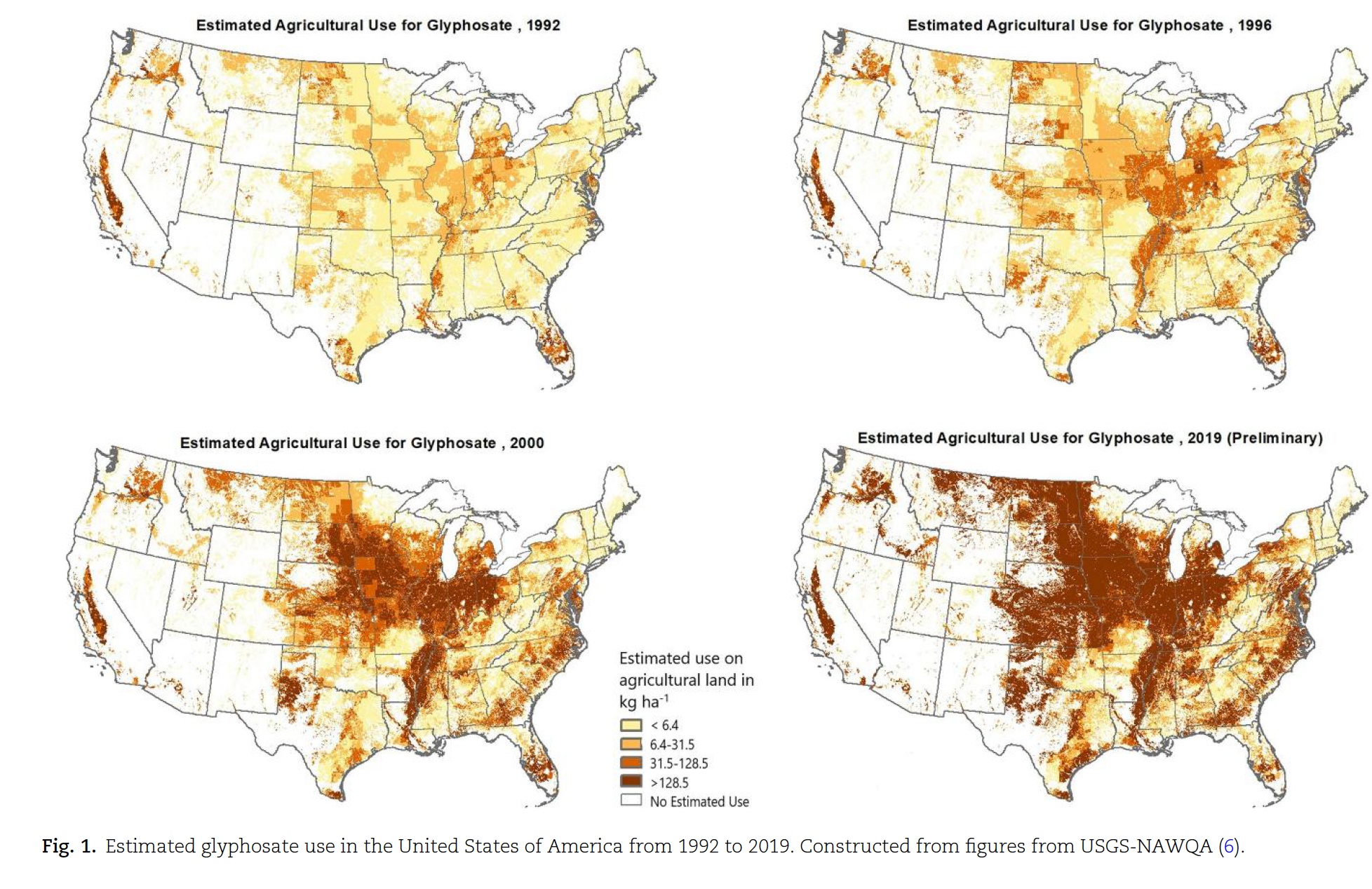

“A diversified and integrated weed control program using a burndown or preemergence herbicide followed by a timely post application reduces the risk of yield loss and slows weed resistance,” Hager says. “This dataset shows loss of weed control over time with post-only glyphosate yet control improved when a preemergence application was used with a post application of glyphosate.”

Widespread herbicide-resistant weeds make achieving acceptable levels of control more difficult. Combined with changes in climate, producing wetter springs and hotter, dryer summers, and it increases yield loss due to weeds. Transformable change in weed management systems is needed.

This initial Illinois analysis showed that late-season control of all weed species, especially waterhemp, drove the most corn yield loss—up to 50% with no weed control. When high-level weed control was not achieved, the hotter and drier weather before silking increased yield loss.

“There are no simple solutions, as no two years are the same and every field is an always changing biological system,” Hager says. “Four-inch weeds can interfere with yield in some years, yet other years it can happen at three weeks after emergence given different growing conditions or weed density or spectrum of weeds.”

In the past, the farmer ‘s mindset was to wait longer than four-inch weeds to allow more weed emergence. But that left millions of unharvested bushels from lost yield potential in Illinois, according to Hager.

To take this machine learning to the next level, Hager met with fellow weed scientists across the Corn Belt, who all agreed to provide their massive HEP datasets. Millions of trials from 24 U.S. and Canadian research institutions were compiled into a single database.

Initial machine learning results quantified the change in weed control efficacy between post-only glyphosate and a pre-herbicide application with post-glyphosate. This huge dataset concluded similar results to those of Illinois: More diversity is needed in weed management systems to slow weed adaptation and prolong the use of existing and future technologies.

Findings included:

“The best weed control to save genetic yield potential is to never let weeds out of the ground,” Hager says. “This unique collaboration between our USDA colleagues and university weed scientists supports what our message has been for a long time. Farmers need to build a strategic integrated weed management system to overcome weed evolution.”

Williams and Hager are excited about what’s next with the future of this enormous dataset. “Now that we have a better understanding of what we can do and look for using the latest analytical approaches on aggregated HEP datasets, the value for direct application to farmers is exciting,” Hager says.

Content provided by DTN/The Progressive Farmer

More information:

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.